On Consciousness and AI

Sparking a conversation

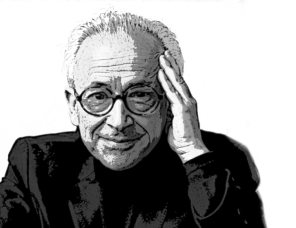

António Damásio, director of the Brain and Creativity Institute at the University of Southern California, is an internationally recognized leader in neuroscience, celebrated for his pioneering work in enhancing our understanding of brain processes underlying emotions, feelings, decision-making, and consciousness. He is the author of acclaimed books such as “Descartes’ Error,” “The Feeling of What Happens,” and “Feeling & Knowing: Making Minds Conscious”.

On Consciousness

António Damásio • Center for Responsible AI Forum 2023

If we were not conscious, we would not be human, and we would not be the way we are. So, obviously, this is an important point.

There is also something very curious, which is an obsession with this theme of consciousness, which comes out in any conversation that you have about AI. So, you talk about Chat GPT, or whatever else that is new in the world of AI, and what people immediately ask is, is it conscious? Will it be conscious? How will we know?

This all sounds like an obsession to me, but it’s important to realize that it’s not a new obsession, because if you go back 75 years, you have probably all heard about somebody called Turing. You have heard about developments in what was not called artificial intelligence then, but were complex computational abilities, and everybody was also concerned with the problem of consciousness, and with how much it would resemble our conscious minds. And, in fact, there’s even a Turing test to check for that possibility. So, these are not new concerns.

Hannah and I, for example, something like 50 years ago, which really dates us, spent a lot of time around Warren McCulloch at MIT, and these were concerns of every conversation. Are these things that we are designing conscious? Can they ever be conscious? So, this is really an important problem.

Now, what is very bizarre, and that’s the only word I can use for that, is that in spite of all these obsessions, in spite of all these intuitions, so little agreement is there to be found on the notion of consciousness. Because if you read most papers written about consciousness, first of all, a vast majority of them don’t even define consciousness. How are we going to make sense of this and of these problems when the definition is not even there? And if there are definitions, the definitions are full of conflict, and there are definitions that many of us would not accept, or certainly I would not accept.

There’s something strange about the fact that we have intuition, we think this is important, we want to check in case machines ever get it, and at the same time, we don’t seem to have an agreement on what consciousness is. And then there’s the issue that when you look at the public, and this is very important for you to realize, when you talk, and many of you here are, like me, scientists, and you will talk to people about consciousness, you have to realize that the public at large, and I’m even talking about the educated public, really has very, very strange ideas about what consciousness is when you hear the term.

For example, I’ve made a list here of at least six different confusions.

One, which is the most common, is that you say consciousness, but people hear mind. People think about mind, that’s what comes to their mind. Then we have, for example, one very clear example where mind is confused with consciousness. Think about our great colleague, David Chalmers. When David first described the heart problem of consciousness, he actually worded it in some way like this. It’s the problem of having a mind, which for him was a non-physical entity, being constructed by a physical object like the brain. So there you have the heart problem of consciousness being defined in terms of mind, not in terms of consciousness. And then we have this other salad, which came from the fact that he had a problem that mind could be physical, and he had a problem that could not be generated out of a brain.

Then there’s another way in which consciousness appears, and that is the thinking and reasoning process. Very often people are saying consciousness, but they’re thinking about reasoning and creativity. One other way which I think consciousness appears when people talk about it really has the possibility of creating narratives.

For example, right now you’re looking at me, you’re concentrating on me, your mental process is in fact geared towards a topic, which is consciousness and this guy here at the table talking. Likewise, I’m concentrating on you and what I want to tell you. But I could be distracted and all of a sudden close my eyes and start thinking about what I’ve done today. And have an internal narrative in which I narrate events of my life, or I start daydreaming about what I want to do tomorrow. This is very often the case, and this also comes under consciousness.

It’s very interesting because this kind of process is exactly the process that has been captured over the years with ups and downs by something that in the brain is called the default mode network. And the default mode network is the way in which we switch sort of offline but still on, in which we talk about ourselves, we think about ourselves rather than thinking about our interlocutor. And it’s very interesting because I am convinced, although my claims or our claims are that most of the process of consciousness and what is most important is really generated by the brain, but generated by the brain subcortically, it so happens that this default mode network and this operation clearly requires cortical processes. And actually, we know where they are. We know that these are mainly midline parasagittal processes that we even know the territories, such as medial parietal cortex and retrosplenial cortex that are critically involved in that process.

Then I have two other sentences that I took out of newspapers. One last week, Picasso’s images are etched in my consciousness. What did the person mean with this? The images of Picasso are etched in his consciousness? Well, not really, but it certainly means that by writing consciousness instead of saying mind, this person was trying to convey that this is a very deep process. It’s very serious. It’s not just my mind every day. And then another one that switches the conversation. The failure of this enterprise is in my consciousness. What do people mean by this? What people really mean is conscience, not consciousness. And here we enter another realm of big problems with the word consciousness. We haven’t even gotten to consciousness. We’re just dealing with the problems with the word.

So, for example, in Romance languages like Portuguese or French or Italian, we have the word consciência really serving two purposes. The purpose of consciousness and the purpose of conscience. So in English, we are okay. But every time you talk about conscienza or we talk about conscience or consciência, obviously you’re dealing with the possibility of an ambiguity. It could be one or the other. And very often when people use the word consciência, they’re not referring to consciousness, but rather to conscience. So you have to be very careful with that. And at least English and German save us from that problem.

Now, when you come to just one more thing about definitions so that we don’t get everybody irate, I think actually philosophers have come out better in terms of definitions of consciousness than neuroscientists and psychologists in general. And it’s certainly philosophers that have called attention more intensely to the problem of feeling. The fact that there’s something that you feel and that there’s something that is important in terms of experience. And that does not come out of the facts at the cognitive level, but rather out of this other process that you define. And it really comes under effect. And obviously, and some of you know our work, so you know that that’s where I’m going. I’m going in the direction of feeling, not in the direction of high cognition. And on that point, what I would like to say is that in spite of that sort of good light that philosophers gave, most of the marking, most of the approaches to consciousness that have attracted tremendous amount of attention have not been approaches that deal with feeling at all, have been approaches that deal with higher cognition. And here, I think it’s quite, you know, it’s to be regretted because by placing consciousness closer and closer to cognitive processes or entirely inserted and resulting from cognitive processes, you have distanced, people have distanced themselves from real life and from the real problem of consciousness. And of course, a lot of the approaches that you hear the most today, say, for example, Giulio Tononi’s, now Bolli and now completed by Christoph Koch, are super cognitive approaches in which there is very little room for feeling. And Stanislas Dehaene, likewise. And in the case of, it’s very interesting because in a response that I deplore, actually, the approach of Tononi and Koch was actually attacked publicly in a letter by other scientists and philosophers, which I don’t think is the right thing to do. But nonetheless, it sort of, to my surprise, showed that at long last, people are a little bit tired of pure cognition in terms of the resolution of the problem of consciousness, which all I can say is, at long last.

I can tell you just a little side story, when Hannah and I in our youth spent time at the Salk Institute, one of our great mentors and friends was Francis Crick. And I’m going to tell you just a little story because it relates to this issue of cognition and affect. Francis, who was a marvelous mentor, we owe him a lot, and was a marvelous friend, was definitely one of the most intelligent and one of the most creative and one of the persons in the world of science that has had the greatest impact on science in our lifetime, without a doubt. And yet when he came to study consciousness, he made precisely the same kind of mistake that I think these people are making.

His reasoning went like this. He was very interested in vision, and we spent hours talking, for example, to David Hubel about vision, and that was really marvelous because the complexities were marvelous, the detail in which we were able to study the retina and visual cortex were completely novel and it created for us a novel world. Francis’s reasoning was that, well, given this tremendous amount of complexity in what we get with vision, consciousness cannot possibly be less complex. Consciousness will have to be as complex or even more complex. And that actually was what led him, with the help of Christoph, to study consciousness via vision. And in fact, one of his first papers was on visual awareness as a way into consciousness.

So it’s interesting, which again, as a side note, tells us that one can be very creative and very bright and very capable, but we all make mistakes, even if we are great and capable. So it’s a good lesson for the young people in the room. We make plenty of mistakes, especially if you have a long life.

Anyway, so I’m going to veer from the cognitive and I’m going to tell you that what interests me the most is in fact the process of feeling. And then I’m going to give you, since I criticize people for not giving you definitions of consciousness, I’m going to give you hours. And I’m going to give you the circumstances in which I think we can talk about consciousness. And now I’m going to read this because it has taken a long time to purify. And this is just a version for this November, probably next month there will be another.

So the processes that guarantee consciousness are, first, a continuous process of feeling, which really means feeling and experiencing, because when you feel, you experience. And that’s the feeling of the organism’s interior. And the feeling that results from this is something that we have in our more recent papers called the feeling of life and the feeling of existence.

Then another condition is the continuous production of imagery. And this imagery is fundamentally exteroceptive imagery. It’s the things that come from vision and hearing and all the other senses that are largely in all of us mammals and, in fact, in most vertebrates, are concentrated in the head. I mean, it’s no mistake that all of these senses are in the head rather than being, for example, in the middle of the hip. It really serves to give a purpose and to give a direction to the processes that we are experiencing. And what is interesting is that this imagery and here, for most of us in this room, it’s visual and auditory imagery.

Visual and auditory imagery is arranged in the perspective of the organism. And because our organisms are oriented with a head and with a point that directs itself towards others and towards the environment, it so happens that we have a natural way of building perspective within our organism. And so you have the perspective, the imagery perspective that is arranged according to the surroundings. And then what is interesting is that when you have the perspective that is generated by feeling, because it’s feeling about your own body, about your own organism, and when you combine that with the perspective that is generated by imagery, then you get something marvelous, which is access to subjectivity.

You generate a subject by having the possibility of feeling your own body, feeling life in you, locating yourself, and you generate a self point. And then you can combine that with the imagery that is coming out of your exteroceptive senses, and then you can generate subjectivity. So it’s how you get to notions of self and subjectivity.

And I also wanted to give you an additional idea to help with the definition of consciousness. I would say that consciousness equals felt experience of life located in one specific organism. Just think about this. If you had a mind without consciousness, you could actually be in a situation where you would not know where your mind is. There’s nothing. I mean, with the definitions of mind that you encounter very often in papers that actually don’t define it, mind could be anywhere. You could be here and say, how would you know that your mind was in your body? You know that your mind is in your body because you feel your body when you’re having a mind. And because you collate that to the fact that your exteroceptive information is giving you a point in space.

Consciousness places the mind in one specific organism. In fact, one poetic way of saying it is that consciousness locates our mind in the universe, happens to be in the part of the universe that our bodies occupy, but it is located in that universe and it guides the life process.

Now, these feelings that I mentioned, I’m going to give you a list because when people think about feelings, unfortunately, the first thing that comes to their minds is emotional feelings, feelings that have to do with all the different emotive processes we have. And this is not what I’m talking about. I’m talking about feelings in the sense that we described as homeostatic feelings. And those homeostatic feelings, I’m going to give you examples. Hunger, thirst, well-being, malaise, pain, pleasure, and desire. Hunger, thirst, well-being, malaise, pain, pleasure, and desire. So, these are all homeostatic feelings. And these are feelings that, by the way, all of us in this room have had several of these feelings today, I would submit. I hope there will be no pain, and be careful with desire. But nonetheless, I think that we’ve had several of them.

But now there are some other feelings that are even worse in terms of their continuity. And I guarantee you that not only have you had these feelings today, but you’re having them right now. And they are the feeling of body temperature, the feeling of breathing, and the feeling of cardiac function. We are having these feelings. And you might say, what are you talking about? Feeling of body temperature? What kind of strange idea is that?

Well, just think of this. Suppose the Champalimaud Foundation had turned on the air conditioning full blast. What would have happened to you? You would shiver, and you would ask the people to change the air conditioning. And you would complain because you were cold. Or suppose the room was overheated, and say, this is impossible to be here, this is very hot. Or suppose you catch the flu, and you have a fever.

So, the feelings of body temperature are absolutely central feelings. You probably are not going to find many references to them in papers on consciousness, because people don’t think about it. But this is critical, and it is one of the background homeostatic feelings that supports our sense of existence. And breathing and cardiac function are others.

So, we have some of these homeostatic feelings that are continuous, and some of them that are semi-continuous. Although, at any point in a day, you are, and in fact, even when you’re dreaming, you are having these feelings. And they’re part and parcel of the background of your mind. And I submit to you that if you did not have these feelings, and there are conditions in which you will lose the possibility of generating them, you actually would not be conscious. This is the backbone of your conscious process.

Now, something that is very important is that these feelings are useful. And this brings us to another very important point in this story, is that sometimes consciousness is not considered a useful thing. In fact, there are theories of consciousness in which consciousness is just there. It’s very complex, it’s very noble, etc. But the idea that consciousness is indispensable to govern your life is not there. Well, our claim is that it is indispensable to guide your life. And if you did not have access to these feelings continuously during a day, you would not have the possibility of organizing your life in such a way that you can survive.

So, feelings are not something that you may have or not have. Feelings are something that are fundamental to organize your experience and to tell you what to do.

Now, you could say, well, why does well-being come into that? You can understand hunger, pain, malaise, but why do you say that well-being is important? Well, well-being is important not only for us, but it’s important for all the creatures throughout evolution as consciousness is being honed in. And that’s because it gives you a license to explore the universe.

So, creatures that are in a state of well-being as opposed to being in a state of pain or malaise are creatures that can go out in the world and explore it. And this is absolutely vital, because when you explore the world, you get to possibilities that you wouldn’t otherwise have. And so, if you combine the possibility of imagery and movement, which allow you to move from one place to the other, and you have feelings to guide your exploration, then you can be a complete person in the sense that a complete creature, living creature, in the sense that you can protect yourself and go on.

Now, the idea of usefulness is very important. What I wanted to… I don’t want to bore you forever. I’m going to try to close soon. I want to give you an idea of how we think this can be implemented neurobiologically. Because, you know, it’s nice to have interesting ideas that people may like or attack, but it’s also important to tell people how we think this could be done biologically.

And how we think it could be done is fundamentally through the process of interception. Now, I know that the neuroscientists in the room will know what I’m talking about, but just in case, we have fundamentally three modes of acquiring information.

One mode that has to do with the world around. You’re seeing me, I’m seeing you, you’re hearing me. That’s extra reception. And, of course, those highly evolved instruments in our head, like ears and eyes, provide information about the world through the images that they form in our cerebral cortices and in a variety of nuclei prior to the cerebral cortices.

But then you have two others that people normally don’t think about. One is interception and the other is proprioception. Now, proprioception I’m not going to talk about, but it has to do with the movements we make and it’s very tied to striated muscle, to the muscles that allow us to move, to walk and also talk, by the way. And there is a way of capturing information from those muscles that is vital to guide the movement that we produce sometimes automatically, sometimes in a very direct way in the world around us. But the most critical for consciousness is interoception.

Interoception is the world around you that allows you to capture what’s inside your organism. It’s not what is inside what’s inside our mouth, or our lungs. It’s what is inside the thick of our organism, our entrails and the thickness of our skins and all the vasculature that is in our flesh. People normally leave that aside, it doesn’t count. But it is absolutely critical. And whether you feel well or not so well, whether you feel full after eating lunch or if you’re hungry, you are capturing information that comes from viscera. And viscera is not just the stomach and the heart and the lungs. Viscera is also, again, that thick under the skin and that thick under the mucosa where you have nerve terminals, highly distributed everywhere in every nook and cranny and that is giving you information about how your interior is. It’s not about the outside world, it’s about the inside world. And this is an inside world that goes to the nitty-gritty of that inside world.

Now, what is very interesting, I’m going to give you two more facts that are critical to understand this. The first is that our relation with that system is very different from our relation to the outside world. Let me explain this. I’m looking at you. And I’m looking at you, and I am getting information from you that hits my eyes, and I gather forms and shapes all around this auditorium. And that comes my way, and I’m not going to do anything to you by return of the post. In other words, when I look at Francisco over there, I capture his physiognomy, but I’m not going to do anything to him at all with my powers as an organism. However, when I capture information from, say, the state of my gut or the state of my lungs, that information is going into the central nervous system, and the central nervous system has a full possibility of replying to that information. Why? Because all of that interior is within the compass of our organism, and the exterior is outside the organism. So within our organism, we have the possibility not only of capturing information from our interior, but responding to that information by return of the post. And when you do that, you have a conversation. And that’s exactly what’s happening with interception.

It’s a conversation between our interior and our nervous system, which is one reason why I get the hives when I hear people talking about, well, the brain will give us solutions to the problem of consciousness. Well, yes, the brain will help a lot, but this is not about the brain only. It’s about a living organism that the brain is in dialogue with. That’s a critical issue here. And if you say, well, prove to us that there’s such a dialogue. Think about when you are in the kitchen preparing dinner, something I never do, but you cut yourself and you have pain. Even if you don’t treat the pain with some kind of analgesic, something that will happen very rapidly is that the pain actually diminishes. And the pain diminishes because your nervous system has gotten information about that and is responding, for example, with a local secretion of opioids that is going to diminish that pain. So there’s a conversation going on. And that conversation is part of what it is to be conscious. It is completely different from the outside world. So this thing, I hope, gives you some hints as to why these distinctions are important.

The other is the very structure of that nervous system, the interceptive nervous system. And it is a completely different world. For example, the kinds of neurons that we have in the interceptive fibers are neurons that actually are very poorly myelinated and sometimes are not even myelinated. For example, we have one very important nerve in our organism called the vagus nerve, and the vagus nerve is 94% of the fibers are not myelinated. This is very different from the kind of neurons that you use to make movements, to talk, to think, to do all of those marvels of cognition and creativity. So this is a very different system at the level of the neuronal structure, the fact that it does not have myelin, which really means that it is not well insulated. You see, the axons of our visual system, for example, are highly myelinated. They are really insulated cables, no leakage. And the operation has to be done at the synapses. But when you are in the fiber of the interceptive system, you can make contacts anywhere along the axon. You are no longer in fully synaptic mode. You are synaptic and nonsynaptic. So it’s different rules. It does not operate by the same values.

One other thing that is very important is that the areas of the brain, whether centrally or peripherally, that are in charge of sending signals into the central nervous system or even within the central nervous system, are in areas that are devoid very often of blood-brain barrier. So the blood-brain barrier… For example, if you take a spinal ganglion, the spinal ganglion has a bunch of neurons, you know, and they are on the way to the spinal cord. But instead of being well insulated from the blood, no, there are gaps, there are fenestrations. And in those areas, you can have the blood interacting directly with the interceptive nervous system. So the term that we like for this is co-mingling of the two areas. By the way, one thing that is interesting, if you look at nuclei in the brain stem, there are several nuclei that are devoid of blood-brain barrier. There’s even one area, which is very critical, called the area postrema. And the area postrema is a circumventricular organ up here. And that area is fully devoid of blood-brain barrier. You know what is very good for you, very adaptive, is that if you eat something that actually will poison you, those molecules are going to be picked up in this area, in the area postrema, precisely because there’s no blood-brain barrier. There’s no separation between the blood circulation and the neurons. And those neurons get, guess what, are going to make you vomit. So when you vomit, you’re protecting yourself. And you only protect yourself because the interceptive nervous system has got this particularity of not being fully insulated from the bloodstream and allowing for this mix, this mix and mess that comes from the lack of blood-brain barrier.

I could spend a lot of time telling you about the very different molecules, the different kinds of neurons and even the different kinds of molecules that are used. The fact, for example, that the interceptive system uses far more monoamines like dopamine or adrenaline or acetylcholine than peptides, whereas the central nervous system uses a whole different variety of chemical connections.

So I’ll close just by saying this. Please give the possibility that feelings that are incredibly important for the guidance of life and that obviously developed far earlier in evolution than the abilities with which you’re listening to me and I’m talking to you, no doubt about that, that feelings are critical to be in this state of consciousness, which simply means that you are aware of what is going on with you and that you are having an experience of what it is being you. And that allows you to connect with the imagery that they are bringing into your brain at the same time in such a way that that imagery is connected to what you are. And that provides you an explanation for consciousness.

I don’t think that the possibility of… I don’t think there is a possibility of resolving the conundrum of experience and of location of mind in relation to an organism if you don’t have this device, and this device is a very natural device. And I would actually just like to tell you about one last thing and to have you meditate on it.

Although many of these things have been obvious to us for a while, especially over the past 10 years, I think our thinking changed in this direction, I would say around, I remember there was a paper that I published with Gil Carvalho, who by the way is a Portuguese neuroscientist and an admirable colleague. And that paper was published in Nature in 2013, I think, or 15, something like that. And that’s when we started talking very intensely about interception and about feeling. Feeling was there before, but we came out of the cognitive into the effect. But the idea was that obviously feelings were providing you with all of this great information, but it was only, I think, less than a couple of years ago that Hanna and I were talking about this and said, isn’t this amazing that people talk about feelings and think about whether they help or not help with consciousness, and yet nobody says this perfectly obvious statement, and that is feelings are spontaneously conscious. So when you have well-being or when you have pain, would you know that it was there if it was not conscious? Of course not. And we talk about this and we don’t say the obvious.

Actually we wrote a paper that came out in Brain, then another one that is in Neural Computation, in which we make the point quite clearly. And now we start with feelings, homeostatic feelings are spontaneously conscious. So nature quite likely got to that point and evolved this apparatus that allowed not only to have a certain configuration of what is going on in your inside, but made it mandatorily conscious at the same time so that you could benefit from it. Because if you were not conscious of the pain and the pleasure and the hunger and the thirst, it wouldn’t do any good to you.

The point that we’re making is that it is good for you. It is something that saves your life, but it’s there telling you in no uncertain terms that I’m here, do what I’m telling you. So that’s it. I’m going to stop right now and I would be delighted to talk more about this. And whatever questions you have about it, I’ll be happy to try to answer. Thank you very much. Thank you.

The Conversation on “The Future of AI”

Conversation on the Future of AI with António Damásio and Arlindo Oliveira moderated by Ana Paiva and Francisco Pinto Balsemão • The Center for Responsible AI Forum 2023